Despite the rhetoric and promises, growing the manufacturing base in America will require more than words and building factories.

With nearly every political cycle politicians decry the shrinking manufacturing base in the United States. They often call out growth in countries like China and Mexico at the expense of U.S. manufacturing. Data is selected and presented that shows a shrinking American manufacturing base, and the supposed increase in imports that are taking away jobs from hard working Americans. They promise to bring back American jobs and use this rhetoric to drum up their base and garner votes. And with the experiences of the last 18 months, the lingering effects impacting global supply chains, shortage of key materials needed for manufacturing, and now inflation, it may sound like the most logical and easy solution to ease these troubles is to bring back manufacturing to American shores. But is it? The answer to that question requires a more thoughtful and serious investigation.

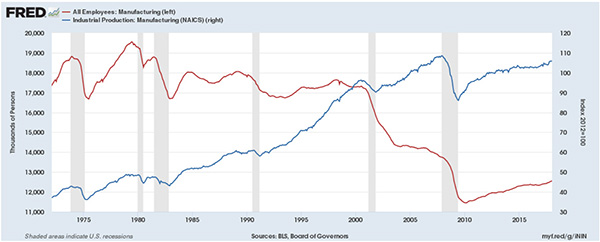

It is true that employee participation in the manufacturing sector in the United States has been on a steady decline since the 70’s and 80’s. But this does not tell the entire story. Based on research by Kevin Kliesen, a business economist at the St. Louis Fed, and John Tatom, a fellow at the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise at Johns Hopkins University, production over that same timeframe has increased significantly. The U.S. worker has seen incredible gains in productivity resulting in a growing manufacturing output. Kliesen and Tatom found that U.S. manufacturing did closely follow economic downturns in general, but to say that U.S. manufacturing is on the downturn is not to tell the entire story.

Another bit of data that is often brought out is the increased imports from China. But are increased imports from China and other countries bad for the U.S. economy and the manufacturing sectors, specifically? Like most Americans, I would have said “yes” until taking the time to research the topic. In fact, what the data shows is that increased imports support an increase in U.S. manufacturing output. Policies designed and enacted to limit imports or make imports more expensive often result in adverse effects for U.S. manufacturing. Making the materials and goods needed for U.S. manufacturing doesn’t drive onshoring, but rather hurts U.S. manufacturing competitiveness.

So, are blanket calls for onshoring beneficial to a strong U.S. manufacturing base? The answer, I believe, is “it depends.” There are certainly areas where one would argue that it is in America’s best interest to maintain a base manufacturing capability. Areas that immediately come to mind are systems related to a strong military and national defense, materials needed to drive communication infrastructure, and the manufacture of medical devices and basic medicines. The latter was brought to light during the COVID pandemic as countries around the world raced to develop vaccines. At the same time, it was reported widely that many of the basic medicines that many Americans needed were manufactured outside the United States. The ongoing issues with the world-side supply chain and the supply of these basic medicines added further fuel to the call for “Made in America” in this industry.

Bringing manufacturing to U.S. shores requires some thought. Putting up buildings and installing equipment are only the first step – and, I would argue, the easiest step. Establishing a competitive and self-sustaining manufacturing operation requires access to adequate raw materials, a robust supply chain, and strong labor. U.S. manufacturing has enjoyed growth because of the increased use of automation and other advanced technologies. These operations require a stable supply chain and labor to operate. U.S. manufacturing has also enjoyed low-cost imports manufactured by countries with lower labor costs. These low-cost inputs have resulted in increased availability of goods not only in the United States, but around the world.

Unfortunately, there is no easy answer. Raised prices on imports, or increased costs following onshoring will likely result in increased costs on goods manufactured in the U.S., which in turn will hurt U.S. manufacturing. Deciding to bring some key manufacturing back to the U.S. in the name of national security may be the right choice but will most likely require government subsidies to be profitable.

The data and research are clear in one regard: a growing U.S. manufacturing sector will rely on a smarter and better trained workforce able to capitalize on automation and the use of data to make better decisions. With this in mind, it seems our best bet for supporting U.S. manufacturing may be in our ability to educate the existing and future work forces to work smarter, not necessarily harder.

Jay Butler is a Senior Consultant with Seraph. Jay has worked in industrial and automotive manufacturing for more than 25 years, including senior positions with Mark IV Automotive, Daimler AG, Brose, and Nissan North America. He has Bachelor’s and Master’s Degrees in Mechanical Engineering from Tennessee Technological University, and a Master’s in Business Administration from The Jack Welch Management Institute. Jay is also a Certified Speaker, Coach, and Trainer with the John Maxwell Team. Jay uses his years of experience to help teams and operations improve their operational and leadership performance.

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.