For manufacturers, identifying new key financial metrics can drive business objectives and provide valuable information for businesses.

By Mary Wisenski, CPA

Manufacturers are extremely precise with the products they make, sometimes measuring down the nanometer. But the mechanics of their businesses can sometimes be a little fuzzier.

Like all businesses, manufacturers track profit and loss, and many adhere to Lean or other frameworks to streamline their operations. There is often a deeper level of financial detail, however, that is not being measured that can provide valuable information for making key business decisions.

This is not a one-size-fits-all consideration since manufacturers can vary so significantly across the industries they serve and products they produce. Yet, all manufacturers should look to these three often-overlooked areas as a potential source of key performance indicators.

Keeping inventory on hand can help fulfill orders quickly, but too much inventory risks stagnation, taking up space and locking up resources. Manufacturers that identify a target inventory level and track how closely they adhere to it are likely to strike this balance effectively.

For some, that target may actually be zero. If you manufacture precision parts or products that are made to order, structuring the business to manufacture on-demand can be ideal. Even customers who order regularly could switch suppliers unexpectedly or change their products, making a part you manufacture obsolete.

A useful tactic for driving inventory closer to zero is issuing quotes for quantities that align with yield quantities. If you produce 1,000 parts per run, consider incentivizing customers toward ordering in 1,000-unit increments. The reverse of this works as well: If a large-volume customer tends to order a certain number of units at a time — say 3337 — design your process to produce 3337 units with minimal waste.

Becoming a just-in-time manufacturer is, of course, the opposite mode of where many manufacturers found themselves during the supply chain issues of the early 2020s. When the availability of materials was sporadic, manufacturers tended to over-order since they didn’t know when they’d have another opportunity.

As we approach the middle of the decade and supply chain disruptions have leveled off, you may be in a position to predict your suppliers’ timeframes with enough precision to eliminate the need for a high volume of inventory — and the risk that comes with it.

If you do find yourself holding on to excess inventory you’re unable to sell, you can convert this inventory into a tax write-off as long as you don’t wait too long. According to US GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles), excess inventory must be written off when it is determined to be obsolete, so manufacturers should evaluate inventory for obsolescence regularly.

Continuing to hold on to excess inventory beyond the point of obsolescence could mean you miss the opportunity to write it off and boost your bottom line. Inventory is considered obsolete when it is unable to be used as intended or sold at its normal price.

In order to take advantage of the write-off, the inventory must be sold/scrapped, donated or destroyed. The first option involves selling the inventory to a salvage yard or liquidator (not just to your normal customers at a discounted rate), which generates a small amount of revenue and allows you to write off the remaining market value. If donated, the inventory must go to a qualifying non-profit organization.

Destroying the inventory should be a last resort. The write-off associated with this route is reduced compared to scrapping or donating, and the IRS requires before-and-after documentation showing that the inventory was indeed destroyed.

Of course avoiding excess inventory should be the goal of every manufacturer. But a secondary goal should be never to miss out on the tax benefits associated with properly processing and documenting excess inventory.

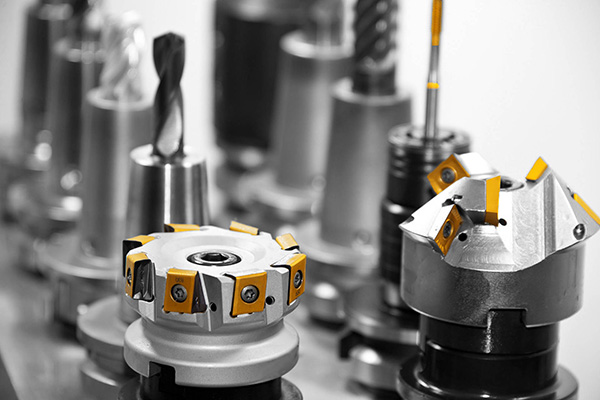

One cost on manufacturer balance sheets I have seen going up dramatically in recent years is machine maintenance. Precision CNC machines, robots and other advanced technology can reduce workforce costs, but their maintenance is often so specialized that it can be both expensive and unexpected.

When a machine valued in the six-, seven-, or eight-figures breaks down, it typically requires a high-level of expertise to fix. If there’s a coolant or oil spill associated with the breakdown, there can be environmental costs as well. These expenses can come in significantly over budget if sufficient resources haven’t been allocated in advance for maintenance.

Manufacturers with a lot of advanced machinery may want to focus on maintenance costs as a KPI for their organization. This makes particular sense for companies that either have a lot of new machinery where there isn’t a long maintenance history on which to base budgeting, or those that have machinery that is at risk of a breakdown may be in need of overhauling soon.

Accurately predicting maintenance costs not only avoids going over budget, but also helps make decisions about the real cost of investing in equipment. The cost of maintenance is also one of many factors that should affect how you calculate the real cost of the goods you produce.

Many manufacturers significantly undervalue the cost of producing their products. They include factors like materials and labor, but neglect to allocate a portion of overhead costs such as utilities, insurance, software, rent or property tax — and yes, maintenance.

Manufacturers looking for a strategic advantage can make identifying the true cost of production a KPI. With this information, they can identify the most profitable products and make sound choices about which lines of business to prioritize.

This requires a fair amount of financial know-how because even a variance of pennies can have a huge impact for a high-volume manufacturer. This type of detailed information can even help facilitate a sale — or derail one if mistakes are uncovered.

An accurate picture of the cost of production can also affect access to capital, since loans can be based on assets. An asset sale is common for manufacturing acquisitions, too. In either case, if your inventory is undervalued, it has an impact.

Mary Wisenski is a partner in the assurance and advisory practices at the Connecticut accounting firm Fiondella, Milone & LaSaracina LLP (FML CPAs).

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.