What is it and where should you use it?

Tantalum Crucible is one of the many industrial forms in which you can find Tantalum (Ta), a dark blue-gray metal found naturally in the earth’s crust. The element is very heavy, ductile, hard, and is highly resistant to corrosion. For this reason, Tantalum and Tantalum Crucible (Ta Crucible) find application in many important scenarios, including high-grade industrial alloys, basically because of the characteristic strength, ductility, and high melting point of the metal.

A good number of industrial processes today need Tantalum. This is where Stanford Advanced Materials (SAM), a Lake Forest California-based supplier of chemicals, comes in. SAM has been in the chemical industry for over 20 years, providing clients with rare earth and high-tech materials such as Tantalum.

However, before considering the unique qualities and applications of Tantalum crucible, let’s take a closer look at Tantalum as an element, it’s occurrence, both of its physical and chemical properties, and general uses.

Atomic Number: 73

Atomic Symbol: Ta

Atomic Weight: 180.94788

Melting Point: 5,462.6 °F (3,017 °C) or 3290 K

Boiling Point: 9,856.4 °F (5,458 °C) or 5728 K

Discovery And Occurrence: Tantalum was discovered in 1802 by Anders G. Ekeberg in Uppsala, Sweden. The metals Tantalum and Niobium were initially thought to be identical elements until 1844, when Rowe and Jean Charles Galissard de Marignac, a Swiss chemist, showed that they were different materials.

In its pure form, Tantalum is a shiny, silver-colored metal that is heavy, dense, malleable, and ductile. These are excellent metallic properties that make tantalum a highly-valuable material for many important purposes. The element is named after the Greek mythological character, Tantalos.

Sources and Extraction: Tantalum occurs in little quantities in minerals, and usually together with niobium as columbite or tantalite. Naturally, the metal occurs in the mineral columbite-tantalite.

Physically, Tantalum is mainly found in Canada, Australia, Brazil, Nigeria, Portugal, Mozambique, Thailand, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Separating Tantalum from niobium can either be by electrolysis or reduction of potassium fluorotantalate with sodium. A common practice is to convert it to its oxide form. Next, the pure metal is obtained by electrolysis of the fluoro-complex, K2TaF7.

Chemical Properties: Tantalum is extremely resistant to corrosion due to the presence of an oxide film on its surface. It is also resistant to acid attack, except hydrofluoric acid (HF) which dissolves it. It reacts with fused alkalis and a number of other non-metals only at high temperatures. At temperatures below 150 °C, Tantalum is chemically inert, i.e., it is impervious to any form of chemical reaction.

Tantalum is useful in any of the following areas.

Tantalum crucibles are essential laboratory appliances made from Tantalum. The metal’s strength, ductility, and ability to withstand high temperatures and corrosion are factors that account for its use in this capacity. Tantalum crucibles are typically available in a variety of dimensions, thicknesses, and shapes.

The following are the most common applications of Tantalum crucibles.

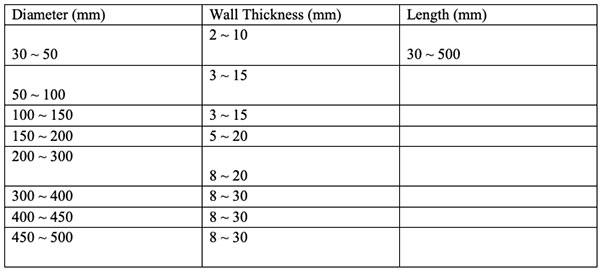

Stanford Advanced Materials, being a trusted supplier of tantalum and a wide variety of tantalum products, offers tantalum crucibles in a variety of dimensions. Depending on what is needed, the material can also be custom-made upon request.

Specifications of SAM Tantalum crucibles.

Jacqueline Owens

Jacqueline Owens is a full-time blogger who regularly publishes a wide variety of business-related content on her blog – from teaching readers how to start their own businesses, from helping them pick the right materials for their offices.

During her free time, Jacqueline spends time at home and cooks different meals for her family.

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.