Despite widespread calls for immediate changes in post-pandemic supply chain operations, companies would be wise to proceed with caution.

With unexpected crises and disasters comes the slew of media commentary about the miscalculations and oversights that led to said disasters or exacerbated their consequences. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought on this flavor of commentary with a heretofore unseen scale and intensity, particularly with regards to supply chain risk. Experts have urged immediate actions to redesign supply chain operations and bring manufacturing back to America. These discussions are not without merit, but in the current atmosphere of fear and remorse there is a danger of changing too much and reacting too soon. Of course, we don’t want to do too little, too late either. Regardless of industry, to get the response just right we will need to exercise some restraint amid the calls for sweeping change. A recommended approach is described here that treats the “adaptation” to a supply chain disruption event like the pandemic the same way we approach the “adoption” of new technology.

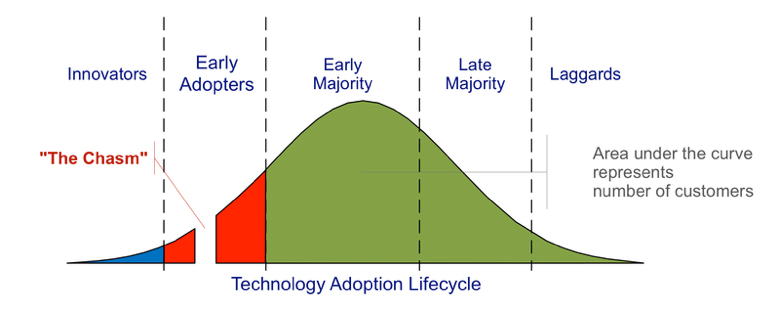

“The Chasm” represents the risk for early adopters. (source: Wikimedia Commons)

In his book Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey A. Moore described the technological adoption cycle, a model that depicts the different stages when different people adopt a new technology. First are the innovators and early adopters who are the first to adopt a new technology. They are followed by the majority (early and late) who recognize the advantages of adopting the new tech but who wait until it is further developed and more widely accepted by their rivals and customers. Lagging behind are the suitably labeled laggards who adopt the technology last and often regret not doing so sooner. Between the early adopters and the majority is a chasm that represents opportunity but also represents risk. In this widely accepted guide to technology adoption, the takeaway is that the majority are wise not to overreact too quickly until more information and more experience becomes available.

We can apply the same approach to our decisions on how and when to react to disruptions like COVID-19 as it impacts supply chain planning. Just as with technology adoption, there is also risk in rushing too quickly to make adaptations in supply chain operations, particularly since many businesses and entrepreneurs are eager to be seen as innovators and early adopters of cutting edge technologies. As devastating as the COVID-19 pandemic has been, we are still steeped in it so deeply that it may be difficult to make objective assessments about the true scale of the disruption. It is natural to feel that changes to supply chain operations must be made since we are directly experiencing the devastating effects of the pandemic domestically, but as of right now, it is extremely difficult to predict what the global long-term consequences of those changes would be.

Another challenge with any large-scale, post-crisis supply chain planning is the manager’s focus on short-term costs and benefits rather than long-term ones. This is somewhat ironic given that the call for change is often framed around the pretext of long-term needs when, in actuality, short-term needs and concerns are the real underlying drivers.

Think twice before making sweeping changes that can’t be undone. (source: iStock)

Another pitfall in post-pandemic planning will be to elevate “low-probability, high impact” factors like COVID-19 so high that they overwhelm the decision making process which should properly evaluate all factors and consequences in a balanced way. In supply chain planning, there are many different factors in addition to risk that are weighed when making decisions including availability, cost, and quality. Either explicitly in tools like a Balanced Scorecard or implicitly in our thinking, each of these have a factor weight, or the percentage of importance given to that factor when making supply chain decisions.

For example, let’s say that in a typical pre-COVID situation the factor weights given to availability, cost, quality and risk were 40%, 30%, 20%, and 10%, respectively. With post-COVID hindsight, it may be fair to conclude that 10% is perhaps too low a percentage for risk. However, this does not mean that companies should now raise it to something as high as, say, 50%. Yet that is the scale of change that a lot of commentary seems to be calling for, similar to overreactions from past supply chain disruptions caused by earthquakes, eruptions, tsunamis, and other low probability events.

The natural tendency after a crisis is to “do something,” but if the risk factor is allowed to dominate supply chain decisions, that “something” would likely be too extreme. It is important to remember that the weight factors that companies typically give to factors like availability, cost, and quality are a result of decades of observation, experience, and research. There were good reasons for prioritizing them in the first place, and over time they will eventually return to their pre-crisis importance. Good strategic decision making requires more caution and restraint and a recognition that the set of primary factors that have heretofore guided our supply chain decisions will likely not change in the long run.

The proper lesson learned from the current crisis should therefore be to increase the weight factor of risk and just-in-case scenarios to a higher percentage but not excessively so. For similar reasons, whatever changes that companies choose to make, they should also lean toward the kind of changes that can later be undone or reversed, fully or partially. Otherwise, those who change too much, too soon may find themselves coming to regret those changes.

Presently there is likely too much uncertainty regarding vaccines, government restrictions, and the future of global trade to begin making informed supply chain modification decisions. But when that time comes, supply chain managers will be faced with difficult “what” and “when” decisions. At one extreme there will be “early adapters that overly weight risk” and at the other extreme will be “laggards that underweight risk”. Between too-much/too-soon and too-little/too-late is a calm, balanced post-pandemic decision that will be just right for your company, industry, and vendor partners.

Richard Kilgore

Professor Richard Kilgore, Instructor in the Online Management and Business Administration program at Maryville University.

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.