Companies seeking to strengthen their ESG profiles need to pay close attention to their supply chains.

By David Simon, Rohan Virginkar, and David Levintow

The new year already is here and, if past is prologue, nearly two-thirds of resolutions have by now been abandoned. If you are responsible for solidifying the “S” in your company’s ESG profile, you cannot afford to fall in with this majority. To do so, avoid the “pie in the sky” resolutions, those that sound perfect in theory but are too vague or unmeasurable to be tracked and eventually realized. Instead, focus on a handful of concrete, actionable, and realistically achievable objectives. Here are four things you can do in 2022 to at least start the human rights compliance ball rolling.

Begin by compiling a list of your company’s 20 largest suppliers, organizing them by location, the type of goods they supply to you, and the cost. Next, build a basic, but reasonable, risk matrix, which assesses the likelihood of a human rights violation and the adverse impact such a violation could have on the business. Doing so allows you to identify those suppliers who might expose your company to legal liability or reputational damage associated with human rights violations. The factors described below are a good place to start, although others may be relevant depending on the nature of your business.

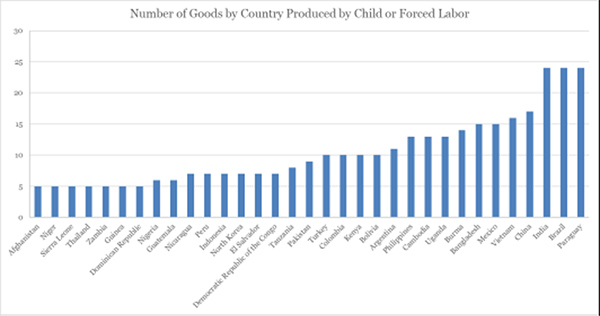

First, have a look at where these suppliers are located or operate. Countries that pose a higher risk of tolerating child or forced labor aren’t too hard to spot:

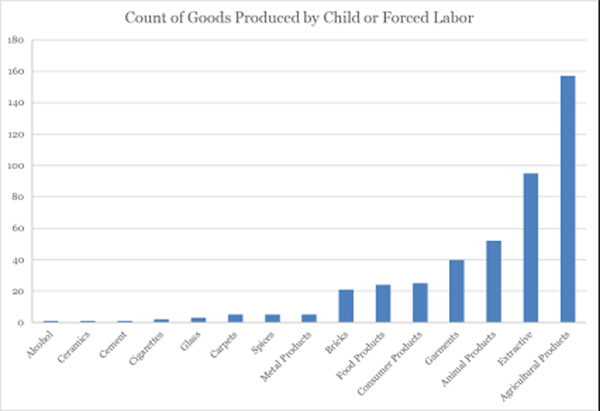

Next, look at the industry in which your supplier operates. What type of products are you purchasing from them, and what are the history and risks of human rights violations historically associated with that industry?

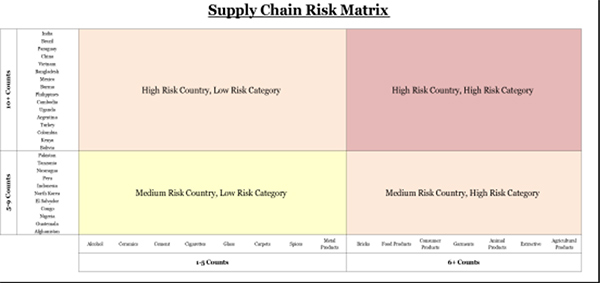

You can combine these two criteria to create a supply chain human rights risk matrix. Here’s one way you might look at it:

Finally, run your company’s larger suppliers through the risk matrix. Voilá – a basic but reasonable risk assessment!

Once high-risk suppliers have been identified, you can conduct some basic due diligence on them to further probe the risk of human rights violations. Here, many companies will already have a serviceable template from which to start: the process used to evaluate third-party intermediaries for purposes of complying with anti-corruption laws such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) or U.K. Bribery Act (2010). The process for identifying forced and child labor risks in a company’s supply can be similar, even though the substance and context are different. Some basic, well-worn due diligence tools include:

Human Rights Compliance Questionnaires: Requiring suppliers to complete a detailed questionnaire is one way to obtain information helpful in assessing the likelihood of human rights risks in your supply chain. Some model questions that can be used for most suppliers are included below:

Reputational Report: Commissioning a background report on higher-risk suppliers can enable you to vet answers provided in response to questionnaires as well, as identify prior associations with human rights violations (or violators), government enforcement actions, or other issues or reports that adversely reflect on the supplier’s reputation.

Red Flag Follow-Up: Investigating any red flags identified in either the questionnaire responses or the background report is a must. For example, a supplier might, without engaging in due diligence, purchase product components from manufacturers in countries with a reputation for human rights violations. Flags come in varying shades of red, and determining the appropriate response requires following up to better understand the facts and circumstances and, potentially, to engage in specific remediation.

A lot of compliance starts and ends with contractual clauses, because these are sometimes the best (or only) leverage companies have with suppliers. We view this as obviously necessary (though clearly not sufficient). Therefore, don’t ignore the low-hanging fruit:

Fortunately, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. The American Bar Association’s Business Law Section has drafted a set of Model Contract Clauses to guard against human rights abuses in international supply chains. Companies should review these provisions and consider inclusion of them when contracts with suppliers are renewed, or when establishing relationships with new suppliers.

The last step is the heaviest lift. As it is in other areas, in order for a human rights compliance program to be taken seriously, it must include some form of continuous monitoring, supported by periodic audits. If you haven’t already started, resolve in 2022 to develop a program that requires suppliers to regularly certify compliance, refreshes due diligence of suppliers on a periodic basis, subjects suppliers to audits through contractual provisions and then follows through by conducting periodic audits, and includes training on relevant laws or company policies. Some hallmarks of a monitoring and evaluation program are detailed in the UN’s Guide to Supply Chain Sustainability:

Effective audits are expensive and time consuming. But here, too, companies can look to vendors for support, as quite a few now conduct ethical trade audits.

Strengthening your company’s supply chain compliance program is a resolution not only worth making but keeping. Adjusting to the increasing scrutiny of human rights compliance is giving many companies headaches. But, as you can see, the task doesn’t have to be complicated. The important thing is to do something and do it right the first time. That way, you will have the right foundation for your program to grow.

David W. Simon (Partner) leads Foley & Lardner’s Government Enforcement Defense & Investigations International Practice. His practice focuses on (1) conducting domestic and international internal investigations to preempt or mitigate actions taken by the U.S. Department of Justice, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and other enforcement agencies, (2) successfully defending companies and senior executives in enforcement actions and litigation with the government, and (3) delivering practical regulatory advice and building compliance programs to help avoid enforcement actions in the first place. David is experienced in guiding corporate boards and company management through challenging government enforcement matters and understands that corporate compliance problems are fundamentally business problems that require business-centric solutions.

Rohan Virginkar (Partner) is a former federal prosecutor and a member of the Government Enforcement Defense & Investigations Practice and Co-Chair of the firm’s multidisciplinary Cannabis Industry team. His practice focuses on advising corporations and executives on government and regulatory actions, conducting internal investigations, leading corporate compliance matters and representing individuals and corporations in white-collar matters and investigations by the U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Attorney’s Offices, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and other domestic and foreign law enforcement and regulatory authorities.

David Levintow is a law graduate in the Litigation Department of Foley & Lardner LLP. David is based in the Washington, D.C. office, where his practice focuses on criminal and regulatory government enforcement, complex commercial litigation, and compliance counseling. David is a member of the Business Litigation and Dispute Resolution Practice Group.

1 The raw data used to create this and the following two graphs were compiled by the Department of Labor’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs (https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/reports/child-labor/list-of-goods).

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.