There’s no doubt the automotive industry is going through a period of disruptive change, as traditional car companies, technology giants, and innovative startups are all looking to play a role in the future of mobility. Winning in today’s market is no longer only about producing and selling cars. Increasingly, it is about providing transportation services and the overall customer experience instead.

As companies jockey for position during this shift, many are finding that their backend supply chain is causing their business to lag. Until recently, the auto industry relied on existing ERP systems and traditional ways of doing business only to learn that they are unable to keep pace with their OEMs, as they increasingly adopt more collaborative and digitally networked environments to conduct day to day business.

Today, the automotive supply chain is typically comprised of an extended global network of suppliers, 3PLs, forwarders and carriers who work off forecasts, schedules and orders communicated by the OEM and cascaded down to each tier of supplier. However, the limitations with ERP and legacy systems mean that most of these communications are done in batch via EDI at best or, worse case, by spreadsheets that are sent by email.

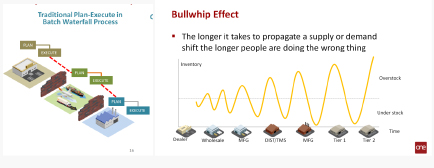

The result is the classic bull-whip effect which leads to excess inventory, parts shortages, and frequent expedites. In fact, it’s not unusual to take over a week for a downstream supplier to sense a shift in OEM demand, as it needs to go through the normal planning cycles before the change is passed down.

To ensure parts availability at the assembly line, companies have also added a patchwork of systems and people -both in-house and/or outsourced to 3PL/4PL/LLPs – to maintain visibility and control of the complex inbound parts flows. Inventory becomes almost an afterthought and a necessary part of the extended network. With extended supply chains, you have no choice but to add buffer points in the form of cross-docks, origin consolidation and destination deconsolidation centers, which leads to even more inventory and a loss of visibility across these locations.

Tracking and tracing a part also requires a lot of effort, because parts are physically distributed globally among multiple parties operating different systems and shipments are tracked at the bill of lading level, not via part number. While the necessary information might be there to connect the dots, the reality is it’s oftentimes not entered consistently and it is incapable of delivering it in real-time.

The problem is legacy and ERP systems were built to plan capacity and materials for only a single plant or organization but not across the hundreds of suppliers and carriers. Other applications have come along to look across organizations on the planning or reporting end, but these options were disconnected from the execution layer and were not presented in real-time.

That’s why the auto industry was forced to employ large teams of “planners” and “control towers” to plan, coordinate material & logistics requests, and monitor to ensure a constant flow of parts supply to the line. It’s not unusual to have hundreds of globally dispersed people or again, outsourced to 3PL/4PL/LLPs and manually piece together information from various systems to keep supply and demand in sync with all impacted parties. Years from now, these setups will be more akin to the switchboard operators that existed before the first generation of computing and automated exchanges disrupted that.

However, the more extended a supply network is the more complex it becomes, which fundamentally increases the risk for disruptions along the way. Be it earthquakes, port strikes, or quality recalls, we have experienced many examples of this in recent years and each have had a huge impact on the worldwide automobile production.

Because today’s systems and processes are not setup to handle these types of disruptions well, when emergencies do happen, organizations are forced to set up ad-hoc war rooms and 24/7 conference calls with partners to resolve. Needless to say, this is an expensive and cumbersome exercise.

For instance, planners often take away the wrong action items and instead of addressing root causes they end up increasing safety stocks and extending planned lead times to try to prevent the next stockout. Also, contract penalties are quite extreme for causing any line downs due to any parts delay or shortage. Each example is contributing to the mindset of keeping excess inventory in the chain. So, while it may appear to be lean inside the plant with JIT and Kanban pulls, the reality is there are a lot of pockets of just-in-case inventory upstream though out the supply chain.

The automotive industry today is running with inventory ranging from 30 to 90 days for OEMs, and 20 to 50 days for top suppliers across the entire network. Due to the current challenges and system imitations outlined above, how much extra cost and inventory are companies carrying today? One of the biggest fundamental drivers of inventory is lead time and lead time variability. What are the potential savings on inventory alone if we can slash information lead times through a real-time digital cloud network?

Digital networks enable the auto industry to:

Some of these what-ifs may sound too good to be true, but similar to the concept of autonomous vehicle introduced several years ago, the technological capabilities are here today and we are seeing rapid development and adoption. If your company is not planning for this future inbound supply operating model, then how will you compete with those companies who have already started this journey? Modern digital networks may be the differential needed to keep up with the increasing demands of your OEM customers.

About the Author:

About the Author:

Rob Choy is VP, Automotive Industry Strategy and Business Development at One Network Enterprises a global provider of a secure and scalable multi-party business network.

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.