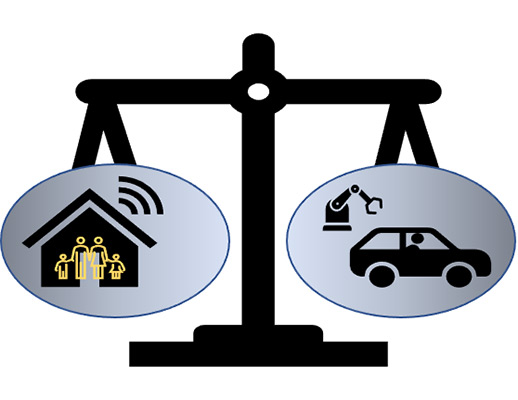

The challenges of remote work schedules are more difficult, if not impossible, in manufacturing due to the nature of the tasks involved.

For many months, we have heard and read about the benefits, even the necessity of, hybrid and/or fully remote work arrangements. If they could afford to do so, pivoting to remote and hybrid work was a common way for companies to adapt during the pandemic. B, but one of the unintended consequences of this has been that many workers not able to work remotely or in a hybrid fashion have felt understandably envious of workers at other companies, or even colleagues at the same company, who have been able to. Every industry has likely encountered this to some degree, including the manufacturing industry.

Despite some very real problems with implementing hybrid and remote work in manufacturing companies, simply ignoring any frustration that employees may feel won’t make it go away. A quite significant factor behind the high numbers of workers leaving their jobs throughout 2021 and into 2022, after all, has been the desire to seek hybrid work arrangements. As a result of this, many managers have been worried about losing good workers if those workers don’t feel heard, and the research seems to validate their concerns. From the perspective of managers in manufacturing, this is a tricky position to be in, but there are potential solutions that can result in win-win situations.

There are some very clear and obvious barriers to implementing remote or hybrid work in the manufacturing industry. Chief among these is the fact that in manufacturing it is necessary for workers to be at the facility where the equipment exists in order to perform the tasks necessary for production. There are certainly some kinds of tasks that could be done online but most manufacturing work, by nature, requires large groups working together to accomplish what the facility is designed for.

Managers who are finding that a significant number of employees are expressing frustration or discontent over not being able to enjoy the same flexibility that other workers do need to explore feasible solutions without compromising the productivity of the facility.

One workplace model that’s been receiving a lot of media coverage lately is the four-day workweek. This is probably due, in part, to the much-publicized pilot program taking place in the UK in which 73 companies are experimenting with a six-month trial of a four-day workweek. About halfway through the program, a survey revealed that 35 of 41 companies who responded expressed that they were “likely” or “extremely likely” to continue the four-day work week arrangement even after the pilot program ends. They’re not alone. Similar experiments in the U.S., such as a 12-week trial conducted by Formstack, have also been deemed successful, with the latter resulting in respectable increases in worker productivity and happiness. Naturally, reports like these have been encouraging for advocates of the four-day workweek.

Generally, the four-day workweek in manufacturing tends to take one of two forms: employees either work four 8-hour days, totaling 32 hours but get paid for 40 hours, or they work four 10-hour days to get in the full 40 hours. Neither of these are ideal for manufacturing as not having anyone work on Friday means losing an entire overnight period when problems that have arisen can be troubleshooted. Instead of four overnight periods as you would normally get with a conventional week, with a four-day workweek you only get three overnight periods—a significant difference.

There are some alternative ways that a four-day workweek could potentially be executed but it would require some nontraditional flexibility and scheduling. For example, one way would involve one group of workers who work four 10-hour days from Monday to Thursday and a second group of workers who work four 10-hour days from Tuesday to Friday.

Another way would involve integrating the three-day workweek. By itself, the three-day workweek would be too radical for most situations, but when combined with the four-day workweek, it could be a way to make the four-day workweek doable for both employees and companies alike. There are different ways to combine the four-day and three-day workweeks, but one way could be to cycle several groups of workers doing four 10-hour days Monday through Thursday with another group doing three 10-hour days on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday.

For example, imagine four groups of workers in which each group works a four-day workweek for three weeks and then, on the fourth week, switches to a three-day workweek from Friday to Sunday. With four different groups of workers cycling through this routine, each group would get 40 hours for three weeks and then 30 hours for the fourth week. This would ensure that each group gets enough hours and still be able to enjoy the benefits of both a four-day workweek as well as a three-day workweek. Meanwhile, companies would be able to avoid the shortcomings of a conventional four-day workweek—or, for that matter, hybrid and remote work.

Regardless of which four-day workweek approach is used, and whether or not any of them are used at all, communication and joint planning between management and labor would be key focused on questions like:

Are employees feeling frustrated about not being able to do hybrid or remote work?

If so, would a four-day workweek satisfy their desire for more flexibility?

Would a four-day workweek even work for the company and its unique situation?

And, of course, proposals like this typically end up in a trial run before the arrangement is made permanent.

With the current high attrition rates in the manufacturing industry, the four-day work week seems to be an idea worth exploring and a solution that could both meet the needs of manufacturers and their employees leaving for the perceived benefits of remote work in competing industries.

Dr. Richard Kilgore is an instructor in the Online Management and Business Administration program at Maryville University.

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.