Volume 24 | Issue 1

By James Wyner, CEO, Shawmut Corporation

Crises often reveal the vulnerabilities of our nation’s free-market system. Take the financial crisis of 2008. During this economic tumult, the open market financial system broke under unforeseen stress when an excessive dependence on mortgage-backed securities and deregulation became catastrophic. As we know, the government stepped in to financially support the banks and, in return, put specific regulations in place to ensure such a problem never happened again.

One could say the government was working to prevent another incident before it occurred. Thus far, it has worked.

The personal protective equipment (PPE) shortage that afflicted critical industries across the country in 2020 began with similar origins at the start of the pandemic. PPE supply chains dried up due to an over-reliance on the most affordable overseas products that came to a production halt as the pandemic ravaged the world.

Many domestic manufacturers stepped in to support the country in this dire time of need and began producing these critically needed supplies, many building operations from the ground up. As during the financial crisis, the government provided some help to support these domestic manufacturers, with grants and short-term production orders. The main difference between 2008 and 2020, however, is that the government has yet to enact regulations that would incentivize buyers to source these supplies from domestic producers.

On his second day in office in January 2021, President Biden signed Executive Order 14001, which directed his administration to report back in six months several steps the government can take to support a domestic supply chain for critical pandemic-related supplies such as PPE, medical supplies and pharmaceuticals. A wide range of domestic manufacturers, healthcare distributors and healthcare providers and stakeholders were invited to give input to the administration’s task force.

While we are awaiting the report, the overseas markets have leveled out, and their products are once again flooding the US, squeezing out domestic supplies with their cheaper and invariably lower-quality goods. As a result, many of the domestic companies that took the risk to step up and provide PPE and supplies during the pandemic have had a more difficult time in the market in 2021 and have pivoted away from PPE, or are shutting down production lines. From a domestic production perspective, we are hardly better off than we were at the beginning of the pandemic. The risks are clear – the US now needs to take proactive measures to prevent another PPE shortage from happening.

While it’s true that the open market has driven American growth and evolution; it has also created a deadly flaw. Market demand for cheaper PPE has pressured industries to take a tunnel, price-driven view to purchasing these life-saving, protective supplies and source primarily from one market — Asia. Where we found ourselves in 2020 was in a chasm between Asia’s ability (and in some cases, desire) to fill our demand pipeline with sufficient supply of finished product and/or raw materials, and the domestic ability to fill the gap in that pipeline.

Even now, there are consistent misses out there between supply chain and need. Before, the US saw widespread shortages of PPE when the spigot of supply from China was turned off. Now, there are organizations and regions with a glut of PPE including N95 masks while others remain starved for these vital materials. And the global shipping crisis of 2021 has exacerbated the problem.

As with the financial crisis in 2008, a free-market course correction has demonstrated that it is not the solution to our PPE crisis. Instead, many organizations have simply gone back to sourcing from the cheapest, often foreign, suppliers leaving our critical supply chains strained, out of step, and vulnerable. Price tunneling is not the answer. Only long-term government contracts, investments, and regulations that allow for a US-made pipeline can solve this problem.

While we are not suggesting that all PPE needs to be domestic, there needs to be a balance that allows for a critical-supply domestic industry to stay strong and vibrant to be able to react when the next pandemic does come. This not only includes the production of the finished product, but as importantly the production of the raw materials as well. It does no good if mask and gown factories are idled due to raw materials stuck on the other side of the ocean if Asian suppliers or global transportation cannot get them to domestic plants. To be sure, some have predicted the global trans issues – lack of containers, port clogging, long lead times – will persist for much longer than the pandemic will.

American-made manufacturing can respond and scale to answer national PPE needs with an efficiency that is difficult for foreign bodies to match. As a result, US-based PPE, including critical supplies such as N95s, can ship to market faster and provide the same or often better quality at a competitive price. Moreover, complete control of the manufacturing process will ensure lasting quality, safety and eliminate potential price gouging. Domestic production will also allow first responders, medical personnel, and other essential workers to work with local suppliers for rapid prototyping and testing of future PPE products.

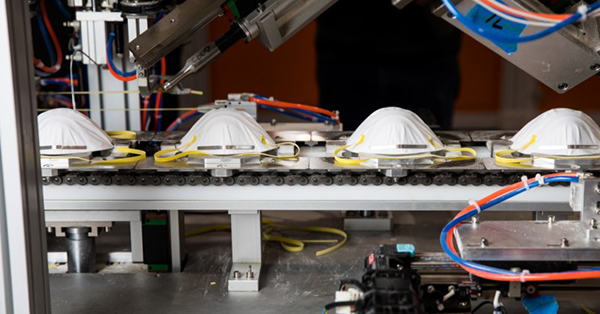

Many critics of Buy American and domestic PPE will tell you there is a price for the locally-sourced quality citing the increased price of an American-made N95 mask vs. one from Asia. But there is a solution to this — innovation. By investing in material and process transformation, robotics and other manufacturing advancements, domestic PPE companies can innovate to compete on price effectively. Much like the billions earmarked recently for the semiconductor industry, the government can similarly help the critical safety and medical supply industry as well.

The industry needs help to build upon temporary COVID-fueled momentum and quickly establish a long-term framework to foster this innovation. And it can be easier than one might think because a regulatory foundation already exists. It’s called the Berry Amendment, a law that requires the Department of Defense to purchase American-made equipment.

The Berry Amendment framework could be extended to critical protective textiles and PPE. As a result, domestic manufacturers would receive the runway, financial support, and commitment required to innovate and compete with foreign suppliers. Long-term contracts from government agencies would give current and future PPE manufacturers the financial commitment needed to innovate and scale their operations to supply for domestic demand from healthcare systems.

If the Berry Amendment cannot be applied more widely, then perhaps legislation arising from EO14001 will step in to provide this assistance. With this regulatory structure in place, American manufacturers can inject proven technological manufacturing methodologies like automation and innovation to drive competitive pricing and unmatched quality.

These steps would incentivize the US-Made PPE industry and domestic supply chains, create US jobs, and help combat future pandemic outbreaks. With that, the US can actively prevent another potential PPE shortage before it becomes a life-threatening issue. America doesn’t outsource its defense equipment, so why would it outsource the creation of life-saving, critical supplies like PPE?

About the Author:

James Wyner is the CEO of Shawmut Corporation, leading supplier of engineered high-performance soft materials and for the Automotive, Healthcare, Military and Protective Apparel markets. In 2020, in response to the Covid 19 Pandemic, Shawmut began producing N95 masks and medical isolation gowns at its headquarters in West Bridgewater Massachusetts and launched a new Health Safety division to create a secure source of high-quality US made PPE.

Prior to Shawmut, James worked for McKinsey & Company, a leading global consulting firm where he focused on both Technology Strategy and Operations work. James holds a BA from Yale University and an MBA from the Harvard Business School.

Contact information:

Mary Katherine Mulligan

mmulligan@tieronepr.com

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.