CCAC Mechatronics Lab

February 4, 2019

By Theresa M. Bryant, Vice President, Workforce Development, Community College of Allegheny County

With a growing disconnect between the skills workers have and those employers need, manufacturing companies are having difficulty hiring a sufficient number of suitable workers. The National Association of Manufacturers recently warned that 2.4 million manufacturing jobs could go unfilled between now and 2028, with the potential for significant consequences not only for individual companies, but for our nation’s economy as a whole.

To address this issue, companies are becoming more expansive in the way they think about worker recruitment and training by experimenting with on-the-job training programs, forming partnerships with educational institutions, and developing apprenticeships and internships designed to build up a pipeline for future hiring. The success or failure of such programs is often determined by their implementation—the structure of the program itself, the background of the people doing the training and the way educational partners approach their mission.

Another challenge lies in the fact that technological advances are transforming virtually every type of workplace. Clearly, companies need to review their training programs and, in many cases, amp them up considerably—for new employees and existing ones. And they need to consider the quality of the results their educational partners are achieving. What factors should companies be considering? What makes an educational partnership effective?

Educational partners must have a strong understanding of specific industries and individual businesses. Apart from their degree and certificate programs, do they have a strong track record of successfully contracting with companies to train workers for specific jobs? Have they had long-term relationships with those companies? Are they able to develop programs with support from industry advisory committees that include leaders in each of the industries they train for?

Our institution’s model enables these committees to share information and analysis among peers, help companies define their workforce needs clearly, and work hand-in-hand with educators to develop curriculum that is on point.

Educators and curriculum developers also need to treat the companies whose workforce they are training like any business would treat its clients. They need to learn the business and listen carefully as executives describe their challenges. Sometimes, for example, even when that conversation begins with a focus on technical skills, it eventually reveals a gap among employees and job candidates in soft skills, such as writing, communication, public speaking or teamwork.

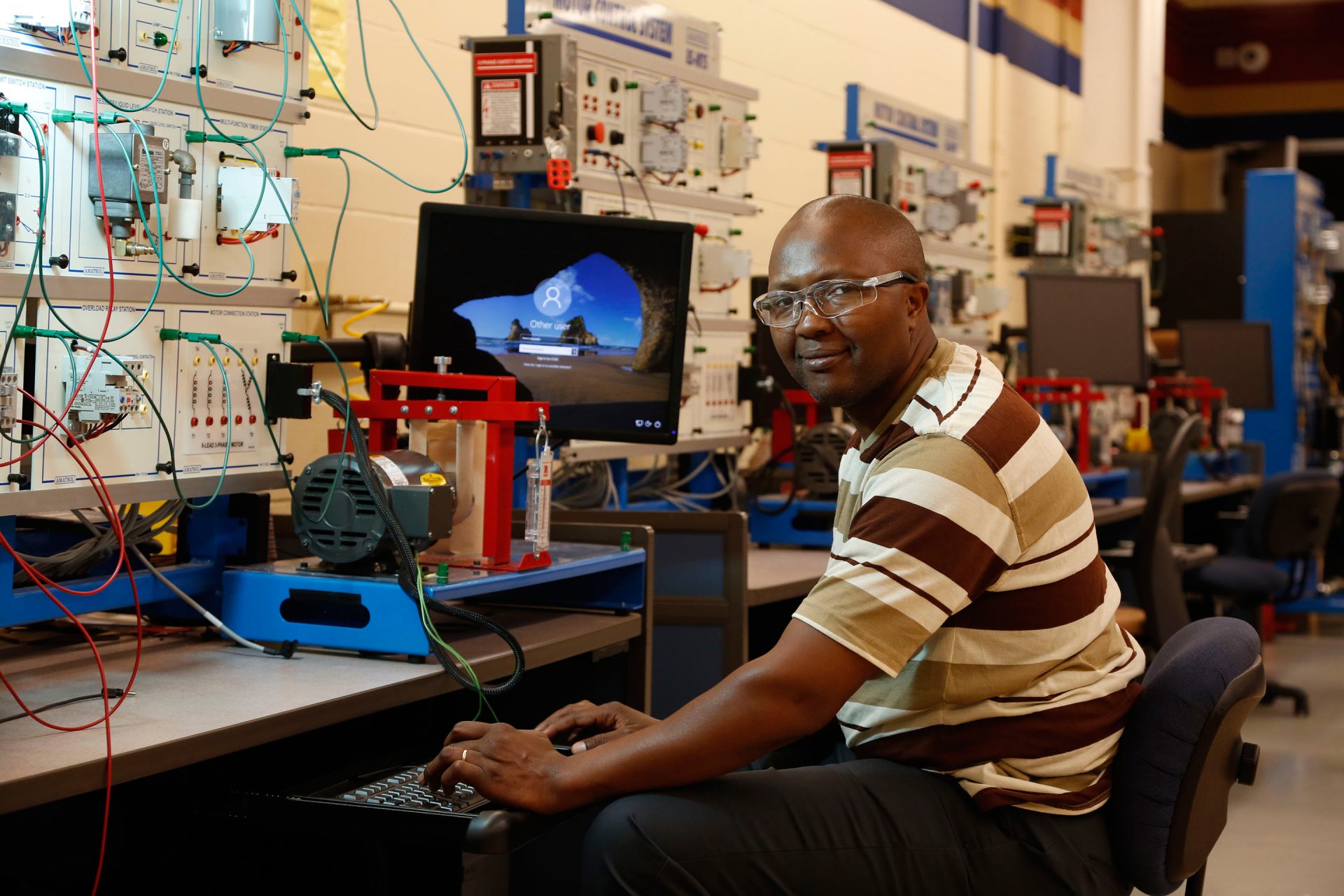

Training programs cannot be conducted solely in classrooms. Sophisticated, state-of-the-art labs are necessary to replicate the types of issues workers will face on a day-to-day basis and to train them to deal with complex technical crises. One example of a training discipline that has utility in many different industries—from advanced manufacturing, to petrochemical, to energy, to logistics—is mechatronics, in which industrial employees learn to work with robots, programmable logic controllers and other automated equipment.

Mechatronics technicians—who are able to install, maintain, modify and repair high-tech systems and equipment—are among the most sought-after workers in today’s highly computerized industrial workplaces, and prospective employers should explore their educational partners’ capabilities in this field, which is proving to be a foundation for many future careers.

In addition, any training program should include the possibility of providing instruction at the employer’s workplace. Whether this takes the form of apprenticeships or simply on-site instruction, giving company supervisors the ability to participate and oversee students’ work can be extremely valuable.

Finally, professional education cannot be a one-time thing. Workers and employers alike need to think in terms of career-long education. Industries change as does the work employees need to perform. Educational partners must commit themselves to constant review and adjustment of their training programs, to evaluate what’s working, what requires improvement and whether their efforts are producing the outcomes desired. Companies need to commit to providing continual feedback and be willing to accept it themselves.

Many industries are facing a workforce crisis that threatens their continued growth. Within those industries, some companies will address that challenge successfully by forging results-oriented partnerships with organizations and educational institutions that can be laser-focused on producing the skilled workers they need both now and for many years to come.

With more than 30 years of experience in both workforce development and continuing education at institutions of higher education, Theresa Bryant currently serves as vice president for Workforce Development at the Community College of Allegheny County in Pittsburgh, PA. Contact: tbryant@ccac.edu

With more than 30 years of experience in both workforce development and continuing education at institutions of higher education, Theresa Bryant currently serves as vice president for Workforce Development at the Community College of Allegheny County in Pittsburgh, PA. Contact: tbryant@ccac.edu

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.