Although the labor market and inflation may stabilize which will provide some cover, the Fed tightening remains a risk.

By: Ryan Sweet, Chief US Economist at Oxford Economics

Fed Chair Jerome Powell sent a strong signal that the Fed’s bias is toward raising interest rates to curb inflation, which is not part of the baseline forecast, nor are we ready to add it. Odds are extremely high that the Fed does hike rates again, but the timing is unclear. Therefore, we are going to wait to make adjustments to the forecast.

The Fed has previously signaled that it plans two additional 25-bps rate hikes. Running this through our model, the impact on GDP, unemployment, and inflation is modest at best. For perspective, each 25-bps rate hike only shaves a few tenths of a percentage point off GDP growth over the course of the year.

Powell emphasized that rate decisions will be made based on incoming data and meeting by meeting, rather than on a preset course. This gives us pause in putting in additional rate hikes. The labor market is showing signs of softening as initial and continuing claims for unemployment insurance benefits have risen while inflation is set to moderate noticeably.

The bias toward additional tightening from the Fed could be attributed to the incoming data that has raised our tracking estimate of Q2 GDP and the diminished risks to the outlook from the debt ceiling. Markets are listening to the central bank. Fed funds futures now apply nearly an 80% probability of a 25-bps rate hike at the July meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee.

The Fed paused in June to assess the economic effects of the past tightening in monetary policy and the recent tightening in lending standards.

A communication issue could be emerging. The next meeting of the FOMC is in July and it is unclear if one month of data, which is mostly lagged, is sufficient for the central bank to answer these questions. The hawkish rhetoric suggests that the pause in June was misguided.

A hawkish Fed does justify our forecast for a mild recession later this year, though the timing is uncertain, but the central bank will break something – inflation, the economy, or both.

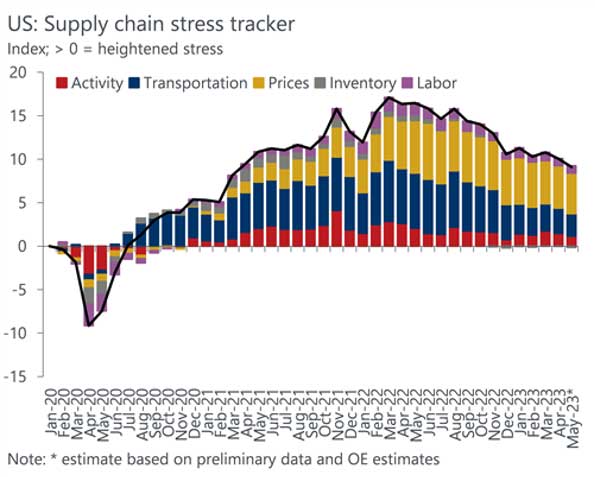

Goods disinflation has been significant this year, as we anticipated. Easing US chain stress has been a key factor. However, services inflation has proved to be sticky this year but is poised to moderate in the second half as nominal wage growth has decelerated and market rents, which feed into the CPI with a long lag, strongly suggest that rental inflation will roll over soon.

Fed officials are unlikely going to publicly say a recession is their baseline, but reading the tea leaves, they recognize they’re facing Hobson’s choice – a mild recession soon or stagflation down the road. Powell’s bias toward further rate increases suggests that he favors a mild recession now because that would be disinflationary.

The Fed needs to tighten monetary policy sufficiently to slow GDP growth below its potential pace to reduce labor demand and put downward pressure on inflation. Therefore, the Fed is signaling that it will err on the side of doing too much to ensure that it kills inflation, at the potential expense of the broader economy. Our baseline forecast assumes the Fed cannot achieve a soft landing or return inflation to its 2% target without pushing the economy into a recession.

The Fed needs the labor market to cool more quickly. Per Okun’s law, a 1-ppt decrease in GDP growth over the course of a year would reduce employment growth by 850,000 jobs per annum. This would increase the unemployment rate by 0.5ppts and shave a few basis points off headline PCE inflation.

The Fed clearly doesn’t appear to believe they’ve done enough to achieve this and will favor doing too much to tame inflation, turning a potential soft landing into a hard one.

The forecast is for the Fed to keep the target range for the fed funds rate unchanged through the remainder of this year, but risks are clearly weighted toward additional rate hikes.

Monetary policy can’t directly impact supply chain inflation. The good news is that supply chain stress has eased significantly despite resilient consumer and business spending, a reassuring development for the inflation outlook. We expect normalizing spending patterns and tighter lending conditions to help loosen lingering supply chain constraints, though there may be some bumps along the way, namely a potential labor strike at West Coast ports.

Ryan Sweet is the Chief US Economist at Oxford Economics. He is responsible for forecasting and assessing the US macroeconomic outlook and how it will influence monetary policy and financial markets. Ryan is among the most accurate high-frequency forecasters of the U.S. economy, according to MarketWatch and Bloomberg LP.

Prior to joining Oxford Economics, Ryan led real-time economics at Moody’s Analytics and was a member of the U.S. macroeconomics team. He was also head of the firm’s monetary policy research, following actions by the Federal Reserve and examining its potential impact on the U.S. economy.

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.