Depending on who you ask, it’s either the best of times or the worst of times for global trade. Protectionists villainize trade as damaging to U.S. workers, while on the other side of the coin pure laissez faire free traders consider trade as a pure positive for the United States.

Mexico and China frequently are labeled as scapegoats for U.S. manufacturing decline. Partially, this is because Mexico and China are currently our top two trading partners, comprising 15 percent and 17 percent of U.S. global trade volume, respectively. In addition, both have lower labor costs than the United States, so the perception is that they have an unfair advantage that leads to a “giant sucking sound” of offshored jobs.

However, losing a job to China is much more damaging for the United States than losing a job to Mexico for three main reasons: The United States and Mexico have conjoined and complementary supply chains in many industries; Mexico generally plays by the rules while China willfully ignores international trade agreements; and trade with Mexico does not aggressively grow the U.S. trade deficit. I’ll break each of these down.

Thanks to policies ranging from currency manipulation to blatant intellectual property theft, from localized barriers to trade to foreign equity restrictions, China ranks second to last on ITIF’s index ranking 56 countries on the quality of their policies and institutions related to maintaining free trade and global innovation. Mexico also scores below average on this measure, but when compared to countries at a similar level of development it does quite well. And its transgressions are much less egregious. Indeed, Mexico is, in the ITIF categorization, an Innovation Follower, a nation that while contributing relatively little to the global innovation system does little to harm it. it. Meanwhile, China is labeled an Innovation Mercantilist, making modest contributions but severely detracting from global innovation. And Mexico has tied the success of its manufacturing industry to fair and open international trade. In fact, Mexico has more free trade agreements with foreign countries than the United States.

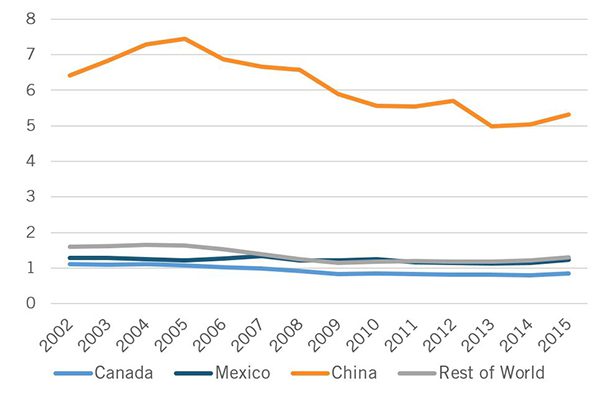

Figure 3: Ratio of Exports to and Imports from the United States, International Trade Administration

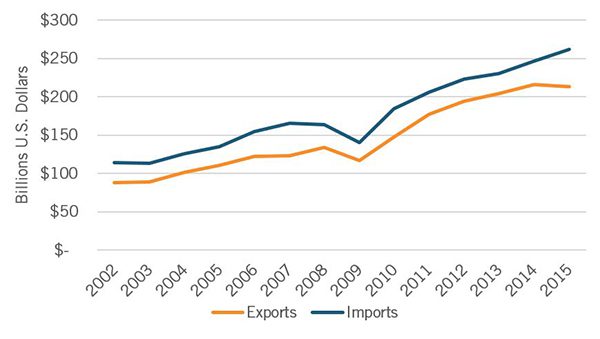

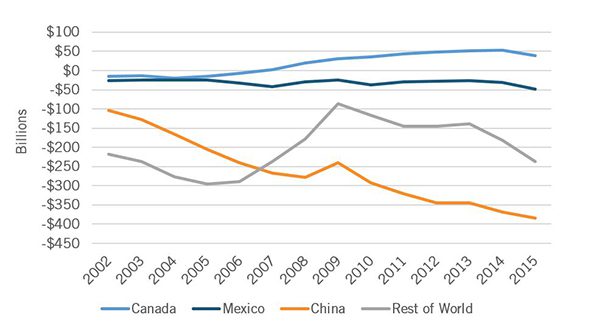

Though the total volume of U.S./Mexico trade has gone up substantially, the balance of trade has been consistently negative but low. China has a very different impact, shipping the United States over five times as many goods as they receive.

In summary, Mexico and China should not be grouped together in the debate over manufacturing, globalization, and protectionism. When a U.S. firm goes to China or is put out of business by competition with a Chinese firm, the United States gains little but loses much. However, the United States and Mexico have a more mutually beneficial trade relationship, and economic activity lost to Mexico is usually made up for in other parts of the manufacturing sector. When a job goes to Mexico, this is generally the result of market forces. Yet when a job leaves for China, often as not, it’s the result of carefully meditated moves by the Chinese government.

The differences in the United States’ relationship with these two nations shows the need for a more nuanced discussion on trade. If the federal government spends it political capital on fighting Mexico, it will be much less able to mount an effective challenge to Chinese innovation mercantilism. In short, the Trump administration needs to choose its battles carefully. Engaging in a “skirmish” with Mexico will mean not enough resources to engage in a “war” with China.

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.