With the UFLPA now in effect, manufacturers and importers need to take steps to remain compliant or risk detention of imports.

By Ginger Faulk

As part of a whole-of-government initiative to combat forced labor in US supply chains, US import authorities are tasked with detaining imports of goods suspected of originating from, or containing content originating from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang), on the presumption that such goods are the product of forced labor. Focusing on certain high-priority sectors, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) recently announced a revamped strategy and enforcement plan targeting imports connected to producers in Xinjiang. Following on the heels of numerous CBP “Withhold Release Orders” applicable to certain products or producers, this summer the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) came into effect at all US ports, establishing a rebuttable presumption that all goods containing content originating from Xinjiang are the product of forced labor and therefore banned from import into the US. This article discusses what manufacturers and importers should be aware of and thinking about now that the UFLPA is in effect.

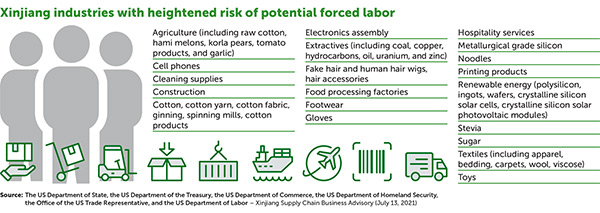

Prioritized sectors for enforcement under the UFLPA are apparel, cotton and cotton products, silica-based products (including metallurgical grade silicon and polysilicon), and tomatoes and downstream products. Solar panels, computer and electronics equipment and other parts containing polysilicon are likely to be impacted, as more than 40 percent of the world’s polysilicon reportedly originates in Xinjiang. Other imports at risk range from cell phones to cleaning products, construction materials to electronics, aluminum alloys and solar panels, as well as products containing copper, oil, uranium, zinc and other extracted minerals.

These new proscriptions add renewed urgency to companies’ obligations to trace Xinjiang-derived content in US supply chains. Meanwhile, CBP is improving its own initiatives and tools to identify and trace goods made in Xinjiang upon arrival at US ports of entry. Recent CBP enforcement initiatives have included multiple “withhold release orders” targeting certain categories of products or specific producers. A new CBP strategy requires a comprehensive risk assessment of Chinese forced labor risks in US supply chains, an evaluation of forced-labor schemes, and coordination with non-government organizations, the private sector and deployment of additional resources and guidance to US importers. To comply with the ban, US importers should conduct a review of their own supply chains for potential connections with Xinjiang and evaluate supplier due diligence in relation to forced labor issues, and related compliance policies and procedures.

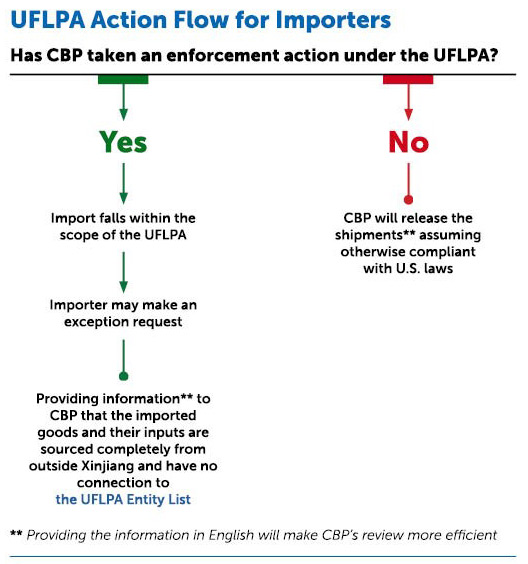

CBP may exclude or detain, seize or forfeit the goods presented to it for importation if it believes the goods contain materials produced by Xinjiang producers or in Xinjiang. The UFLPA establishes a rebuttable presumption that all goods mined, produced or manufactured wholly or in part in Xinjiang were made with forced labor; therefore such goods will presumptively be denied entry into the US. This presumption applies to goods that contain any level of materials produced with forced labor and at any level of the supply chain. For instance, CBP may deny entry to an article that was made in and shipped from a third country if CBP suspects that the item contains fibers, minerals or other content from Xinjiang

For any Xinjiang-linked product, importers will be required to demonstrate with “clear and convincing evidence” that the imported goods were not mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part by forced labor. This requires the importer to provide a detailed description and process and geographical maps of the entire supply chain for the imported goods and each of their components, across all procurement and production phases, as well as a list of all upstream producers and supporting documents.

For any Xinjiang-derived content, the importer must also provide a complete list of all workers at the producing entity, including:

Appropriate evidence may include: supplier affidavits; purchase orders, invoices and proof of payment; a list of production steps; transportation documentation, daily manufacturing process reports and evidence of a supplier’s labor compliance program.

There is no de minimis exception – in other words, any amount of content suspected of being the product of forced labor will trigger the import ban.

CBP will rely on the US Department of Labor’s (DOL) List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, List of Products Produced by Forced or Indentured Child Labor, and Better Trade Tool, as well as the US Department of State’s (DOS) Trafficking in Person Report and Responsible Sourcing Tool, to help identify targets and implement the UFLPA.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) also recommends that importers use DOL’s Comply Chain as guidance for developing and demonstrating due diligence in the supply chain.

Namely, due diligence processes should include procedures for

DHS Guidance provides that effective supply chain mapping “requires each product input to be packaged, processed, and traced separately from other product inputs or modifications throughout the supply chain. Most importantly, it does not allow any commingling of product inputs at any point in the supply chain.” Importers will need to document the procurement and production processes – all the way from raw materials to finished goods, listing all entities and locations involved, including processes that were in-house as well as partially or wholly outsourced, and the relationship between the entities involved.

The US government’s “UFLPA strategy” points to the complexity of global supply chains and limited transparency as a central challenge in complying with the UFLPA. Commingling of Xinjiang materials with inputs from other regions can obscure the origin of materials. Compounding the problem, CBP notes that some companies, including Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, have attempted to transship goods to other locations in order to conceal their origin. Meanwhile, manufacturers in China may face pressure and threats of retaliation from Chinese authorities for efforts to comply with the US import laws.

In anticipation of these enhanced enforcement attention by CBP, US importers are advised to evaluate current supply chain and import practices against the requirements in the new law, recently announced USG import compliance standards, and global standards. This means reviewing, among others, a company’s procedures for supplier due diligence, supply chain tracing and supply chain management.

Importers should also evaluate their procedures related to documenting global production and materials procurement to ensure that their goods do not contain Xinjiang-derived components. These reviews should result in concrete actions and recommendations to fill in gaps in supply chain tracing and documentation. In addition to preventing import violations and preparing proactively to respond to any potential CBP enforcement actions, conducting this sort of procedural systems review demonstrates to regulators, investors and third parties a company’s commitment to eliminating forced labor from its supply chain and fully complying with US import laws and regulations.

Ginger T. Faulk is a partner at global law firm Eversheds Sutherland, where she advises multinational companies in matters involving US government regulation of foreign trade and investment. She has extensive experience advising and representing global companies in the energy, defense, aerospace, telecommunication, software and other high-tech industries, counseling clients in matters arising under US sanctions, export controls, import and other national security and foreign policy trade-related regulations.

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.