A looming recession is clouding the near-term outlook, but the boom in factory construction is a sign that brighter times lie ahead.

Incoming data suggest the US economy remains resilient in the face of mounting headwinds, but a recession still looks more likely than not later this year. Inflation is slowing, but core remains sticky, which will force the Fed to keep rates elevated. The full impact of that tightening has yet to bite. The hit from higher rates is rippling across the economy, having already dealt a blow to housing market activity, and manufacturing is currently in the crosshairs. The strength of consumer spending, particularly on services, has so far been enough to prevent the broader economy from entering recession, but with the labor market set to weaken in the second half, that could be running on borrowed time.

Three global trends are weighing particularly heavily on manufacturers. High interest rates naturally take a bigger toll on the capital-intensive manufacturing sector. The fading legacy of the pandemic is a headwind, as consumer spending shifts back away from goods and towards services. Finally, the supercharged inventory cycle of the past few years as supply chain problems eased is shifting from boosting to dragging on growth. The US did at least dodge most of the war-related surge in natural gas prices last year and the ongoing uncertainty of future supplies, but the US looks like the cleanest shirt in the dirty laundry.

While expectations have brightened in recent months, evident in buoyant stock markets, the more positive tone of the forward-looking business surveys, and upward revisions by economists to their forecasts, I suspect that optimism will prove to be premature. Falling inflation means the Fed may now be done raising rates, but the economic impact of those increases is only felt with a substantial lag. A prolonged drag on credit standards due to the banking turmoil earlier in the year will add additional downside. Therefore, a recession still appears more likely than not later this year, though I do think that is likely to prove mild by historical standards – more like the early 90s recession than 2008 or 2020.

Despite my gloomy outlook for the broader economy over the next year or two, readers may be surprised to hear I am actually more optimistic for the future of US manufacturing than at any point over the past decade.

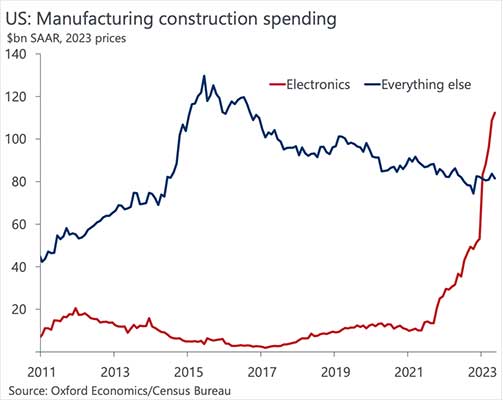

The reason is the new wave of supply-side industrial policy we’ve seen, with the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act that passed last summer spurring a sharp rise in investment in new manufacturing plants. The scale of the increase has been truly staggering, and the official economic statistics have struggled to keep pace in real time – the data have been persistently revised higher over the past year. Spending on factories has doubled over the past 18 months to close to $200bn annualized. To put that in context, the US is now spending as much building factories as it is offices and commercial buildings such as malls, restaurants and warehouses combined!

The entire boost to construction has been in electronics plants which have benefited from the considerable subsidies on offer for semiconductor chip fabrication and electric vehicles with American-made components. Outside of electronics, spending on factories has continued to trend lower in real terms.

That is already supporting demand for construction equipment and materials, but the bigger boost will come once those factories begin to come online, boosting demand for a wide range of intermediate inputs.

With the boom in structures investment limited to just a few specific industries, seemingly in response to large subsidies from the Federal government, it would be wrong to interpret this as a widespread return of manufacturing to the US. With modern factories operating with fewer employees than in the past and wages are no longer much higher than in the rest of the economy, the implications for the workforce will be more limited.

Nor is industrial policy without its costs. US activism has encouraged similar subsidies from other governments, which will weigh on export demand for US goods. While the direct subsidies are good news for the narrow range of sectors that benefit, that money could arguably have delivered a broader boost to manufacturing if it were invested to help tackle problems faced across industry, notably investments in education and training to help overcome a lack of qualified workers.

However, the surge in factory construction does mean that, once the current economic slump is behind us, the outlook for manufacturing sector over the next five to ten years is brighter than it has been at any time than in the past few decades.

About the Author:

Michael Pearce is lead US economist at Oxford Economics based in New York City. He has spent over a decade analyzing the US and global economy and has degrees in economics and economic history from University College, London and LSE respectively.

Scott Ellyson, CEO of East West Manufacturing, brings decades of global manufacturing and supply chain leadership to the conversation. In this episode, he shares practical insights on scaling operations, navigating complexity, and building resilient manufacturing networks in an increasingly connected world.